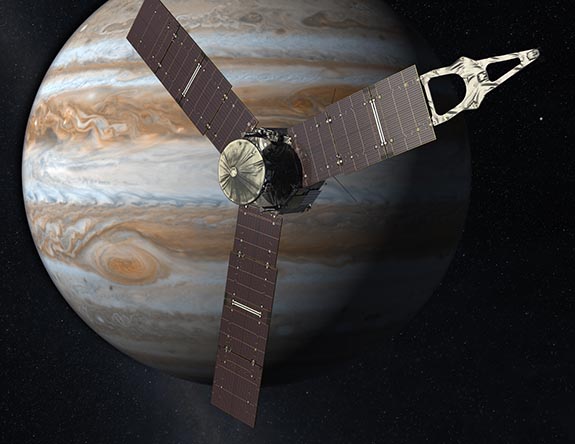

Earlier this month, NASA’s Juno space probe successfully entered Jupiter’s orbit after a 365-million mile trek that took nearly five years. For the next 20 months, Juno will discover what’s hiding under the planet’s thick clouds and transmit that information back to Earth. Don’t be surprised if Juno encounters diamond crystals the size of hailstones along the way.

Two prominent scientists — Dr. Kevin Baines of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Mona Delitsky from California Specialty Engineering — made headlines three years ago when they floated the idea that diamonds rain on Jupiter.

In 2013, at the 45th annual meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society, they outlined the circumstances under which Jupiter’s atmosphere would rain down thousands of tons of ring-sized diamonds every year.

It all boiled down to chemistry…

Many readers already know that the Earthly diamonds form naturally when carbon is heated to an extreme temperature and put under intense pressure about 100 miles below the surface. The diamonds find their way to the surface via kimberlite pipes — the equivalent of volcanic superhighways.

While diamonds on the Earth come from the bottom up, diamonds on Jupiter come from the top down, say the scientists.

Baines and Delitsky believe the tremendous gravitational pull of Jupiter results in a super-dense atmosphere of extreme heat and pressure — the same conditions found deep within the Earth.

Lightning storms in the upper atmosphere of Jupiter are responsible for initiating the process that eventually yields a diamond. When lightning strikes, methane gas is turned into soot, or carbon.

“As the soot falls, the pressure on it increases,” said Baines. “And after about 1,000 miles it turns to graphite — the sheet-like form of carbon you find in pencils.”

As it falls farther — 4,000 miles or so — the pressure is so intense that the graphite toughens into diamond, strong and unreactive, he said.

The biggest diamond crystals falling through the atmosphere of Jupiter would likely be about a centimeter in diameter — “big enough to put on a ring, although, of course, they would be uncut,” said Baines.

Because Jupiter is made of gas and is hotter than the Sun at its core, what happens next to the falling diamonds is the saddest part of the story. As they descend another 20,000 miles into the core of the planets, they eventually melt into a sea of liquid carbon.

“Once you get down to those extreme depths, the pressure and temperature is so hellish, there’s no way the diamonds could remain solid,” he said.

In 2013, skeptics asked Baines, “How can you really tell? Because there’s no way you can go and observe it.”

At the time, he answered, “It all boils down to the chemistry. And we think we’re pretty certain.”

Now, with Juno on Jupiter’s doorstep, we may know for sure…

Credit: Illustration courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech.