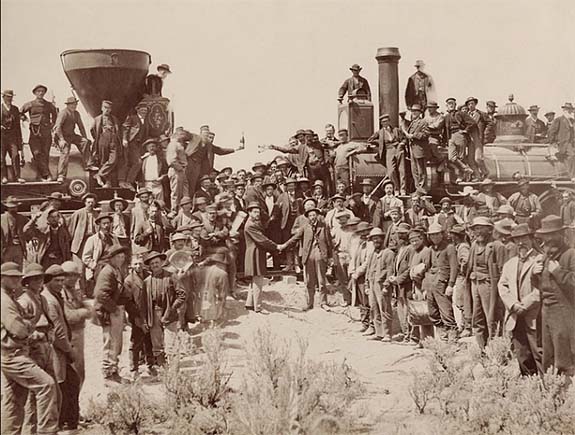

This past Friday marked the 150th anniversary of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, an epic project that spanned six years and 1,800 miles, with the Central Pacific Railroad working from west to east and the Union Pacific Railroad from east to west.

When the two railroad lines met at Promontory Summit, Utah, on May 10, 1869, the engineering marvel was culminated with railroad magnate Leland Stanford driving the ceremonial final spike — a glistening symbol made from 14 ounces of 17.6-karat gold.

As Stanford gently tapped the copper-alloyed spike through a pre-drilled hole in a special tie of polished California laurel, a famous telegraph announced the news in real-time: “The last rail is laid. The last spike is driven. The Pacific railroad is completed. The point of junction is 1,086 miles west of the Missouri River and 690 miles east of Sacramento City.”

Celebrations ensued from coast to coast.

“It psychologically and symbolically bound the country,” Brad Westwood, Utah’s senior public historian, told the Associated Press.

The Transcontinental Railroad united a nation recovering from the Civil War and laid the foundation for its growth, economic progress and improved way of life. A coast-to-coast trip that once took six months, could now be accomplished in 3 1/2 days.

The accomplishment also symbolized American ingenuity and technical achievement, which was, at the time, as spectacular as landing a man on the moon. Incidentally, the first moon landing would take place 100 years later on July 20,1969.

The idea of using a golden spike to commemorate the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad was the brainchild of David Hewes, a San Francisco financier and contractor.

The spike is engraved on all four sides.

One side says, "The Pacific Railroad ground broken January 8, 1863, and completed May 8, 1869." A second side says, "May God continue the unity of our Country, as this Railroad unites the two great Oceans of the world. Presented by David Hewes San Francisco." The third and fourth sides list the names of the railroad directors and officers involved in the project.

Interestingly, the date on the Stanford spike is wrong because the celebration had to be delayed two days due to bad weather. Fearing that the golden spike would be stolen if it was left in place, Stanford (who would later establish Stanford University) extracted the spike from the laurel tie and brought it back to California. Today, it resides at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford.

A duplicate golden spike, which was engraved later with the correct date, became the property of the Hewes family. That spike is on permanent display, along with Thomas Hill's famous painting "The Last Spike," at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento.

Throughout this past weekend, revelers celebrated the historic meeting of the rails at Golden Spike National Historic Park northwest of Salt Lake City. Visitors came from far and near, decked out in period attire, including top hats and bonnets.

Other celebrations throughout the state included art displays, musical performances, historical exhibits, storytelling, lectures, community festivals, parades, film screenings, model train shows, historical site tours and reenactments of the golden spike ceremony.

Credits: Photo of "duplicate" golden spike by Neil916 at English Wikipedia [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. "The Last Spike" painting by Thomas Hill [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Photo of Samuel S. Montague, Central Pacific Railroad, shaking hands with Grenville M. Dodge, Union Pacific Railroad, by Andrew J. Russell [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Modern reenactment photo courtesy of the National Park Service. Utah state coin by the United States Mint [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.